This afternoon I’ve been perusing various Youtube videos on Ashtanga Yoga looking for inspiration when all of a sudden I got what I was looking for. I came across this video in which Richard Freeman, a well-known Ashtanga Yoga teacher, is speaking on a panel at the Urban Zen Well Being 2007 Forum. What struck me about that clip was that he was making the point that “it’s no longer the age of the guru;” in fact, a new model is being born in the West in which the relationship of student to teacher is one of “equal partnership on both sides.” In this article, I intend to explore what the traditional guru-disciple relationship was like; how it is no longer valid in this day and age; and what we might replace it with.

The Guru-Disciple Relationship

The role of the guru dates back to the period of the Upanishads, around 1000 B.C.E. Prior to this period, Hindu spirituality was expressed in the act of sacrifice to the gods. The gods were thought to be outside forces that needed to be manipulated in order to maintain order. The Brahmans (priestly caste) were in charge of maintaining the spiritual order in the form of sacrifice.

But by the ninth century, a new revelation began to be expressed. Instead of gods, like Shiva or Brahma, dwelling outside, the gods were considered inner experiences, inner energies that could be met and used for personal transformation. Anyone could, now, have a direct access to the gods. It wasn’t just the Brahmans (priestly caste). The term "Upanishad" derives from the Sanskrit words upa (near), ni (down) and şa (to sit) — so it means to "sit down near" a spiritual teacher to receive instruction in discovering these powers within.

The role of the guru was to illuminate the shishya (disciple) from the darkness of illusion through esoteric knowledge. Gu means to dispel. Ru is the darkness of ignorance. In order for this new revelation to be expressed, the guru’s knowledge needed to be vast. He needed to have been someone who had already awoken from the dream of maya (illusion), awake to the direct experience of the purusa (indweller, soul). Additionally he needed to have been a shishya of a guru, himself and to have received his guru’s blessing to impart the wisdom.

Hierarchical Roles

The role of the shishya’s was primarily devotion, commitment, and obedience. In exchange, the guru taught through discourse, through silence, through medicine, and through imparting esoteric practices. The guru offered what he could to illuminate his disciples into the truth, knowledge, and experience within. But the role was hierarchical. The shishya was in the hands of his guru. If the guru took advantage of his position, then that was the risk the disciple took.

In Aṣṭadaḷa Yogamālā: Articles, Lectures, Messages by B. K. S. Iyengar, the author describes the brutality, at times, of his guru, T.K.V. Krishmacharya, how “his moods and modes were very difficult to comprehend and always unpredictable. Hence, we were always alert in his presence. He was like a great Zen master in the art of teaching. He would hit us hard on our backs as if with iron rods. We were unable to forget the severity of his actions for a long time.” (Iyengar, B.K.S. Aṣṭadaḷa Yogamālā: Articles, Lectures, Messages. Mumbai: Allied Publishers Private Limited, 2006. Print. p. 53)

And in an interview I dug up in my files dating back to 1993, Pattabhi Jois says this about his guru:

My guru was a very difficult man…One example of his callousness, which I tell about is this: on the Sanskrit College’s anniversary day a large celebration was staged which the Maharaja attended. We were to give a demonstration on the ground…There was no podium so my guru told me to do kapotasana (an extreme backbend) and stood on top of me for 10-15 minutes giving a lecture. There was a small tree coming out of the ground that had been haphazardly cut several inches from the ground. The sharp end of the stick stabbed into my shoulder and stayed there, penetrating more and more deeply as the lecture went on…After the lecture I stood up and was covered with blood…For 15 days I could not move my arm.

Imagine the lawsuits that might have taken place had Krishnamacharya been teaching at the local Yoga studio these days? Clearly, times have changed.

Guru Projections

We in the West have an awkward relationship with this sort of authority. We tend to think of the guru-shishya relationship as one of projection. The shishya abdicates power to the guru by projecting all things parental onto him.

I saw this, and even experienced it, first hand when I studied at Pattabhi Jois’ Ashtanga Yoga Nilayam throughout the 90s. Guruji could play the face of our good father quite well. He could also be the fierce father, the tender father, the wise grandpa, and many, many more. Much of the relationship we shared with our guru depended on our unfinished business. In a lot of ways, many of us were working out our daddy stuff with him, whether we wanted to admit it or not.

Today, I have little doubt that most of the projection I had with him had almost nothing to do with who he actually was, but being a great teacher, he willingly took on the various fatherly roles and allowed us to act them out with him in order to move through some of the leftover childhood stuff. While a lot of us got great benefit from this form of relating, I saw some of my fellow guru bhai (disciple brothers and sisters) leave the practice altogether because they could never separate the projection from the man that he was. And some left because when they did, they were sorely disappointed.

Guru or Snake Oil Salesman?

But unlike an authentic guru, who is regarded with great respect in his culture, our teachers in the West are looked upon with a degree of skepticism. We do not have the same opinion of the spiritual dimension that Asian cultures do. In the audio CD, The Roots of Buddhist Psychology, Jack Kornfield describes the experience of being a monk in Thailand and accepting alms from people who could barely feed themselves. The work of the monks was so important and valued, that the lay community would starve to feed them.

We, in the West tend to hold people of spiritual authority, with doubt and distrust. Fundamentally we resist being conned. It is not uncommon to see leaders of spiritual movements initially elevated by their followers and eventually disgraced by those same people. Just look at the recent John Friend-Anusara Yoga and Diamond Mountain University scandals. I don’t know the inside scoop, but what’s clear is that students revere their teachers as if they were gods and then they, somehow, fall off the pedestal. They're human.

But we as a society tend to hold people who run or lead spiritual movements to a higher standard than we hold even our politicians. Because they’re leading us into spiritual practice, they have to be unblemished by any one of the seven deadly sins; in fact, in some way or another they need to be perfect.

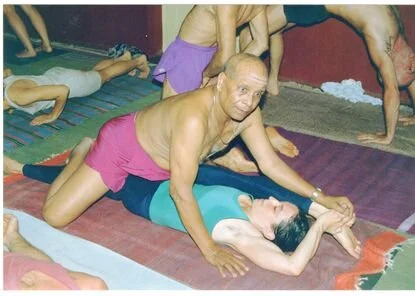

However, when you look closely at the lives of some of the great teachers from the East, the so-called illuminated gurus, what we’ll find is nothing but humans, people steeped in tradition and teaching and, at the same time, riddled with human foibles. Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, the Tibetan spiritual leader that founded Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, had the reputation of drinking beer all day long and had quite an appetite for young women. Osho, also known as Bhagawan Shree Rajneesh, the founder of Osho Ashram and Rajneeshpuram in Oregon, was addicted to nitrous oxide and also was known for his affairs with his female disciples. Amrit Desai, the yoga master who founded Kripalu Institute, had to resign as director after his multiple extramarital affairs were exposed. My own yoga teacher, Sri K. Pattabhi Jois, publicly fondled his female students genitalia.

Does that make these men any less spiritually advanced? We in the West would like to think so. It’s quite possible that we want to believe that our spiritual leaders represent the perfect parent, the one we didn’t grow up with. The truth of the matter is that we all make mistakes, sometimes even very big ones, ones that hurt others badly. I am thinking, at this moment, of the priests who mistreat(ed) children. Without a doubt, this behavior is inexcusable; however, it demonstrates that we can no longer afford to completely relinquish our power to the charismatic individuals that lead our spiritual movements.

God is Dead

These people are human, just like you and me. Perhaps there was a time when there were gurus who were truly unblemished, but we’re living in a very different period, historically speaking. When Nietzsche said, “God is dead,” what he meant was that we can no longer rely on the church, the mosque, the monastery, the lama, the guru, or even a philosophy for our salvation. For him, these forms of authority had become completely discredited. As a result, it was up to each of us to find our way.

I am not suggesting that we do it alone. We need others to support our growth and development, but when we are always looking for the wisdom, the compassion, and the answers outside of ourselves, we forget that we're just projecting.

It can help immensely to love and revere our teachers while simultaneously never forgetting that that which we love and revere is The Self. Essentially, what I am arguing is that when we take the projections back, when we take responsibility for our own transformation, we stop the game of elevating teachers or the spiritual lineages we come from in a way that does not serve us. Likewise, we also stop being disappointed when our gurus turn out to be human, just like you and me.

Not everyone who comes to spiritual practices, like yoga, looking for the full-promise of yoga. Many just want to get stronger, feel better, or have a positive group experience. There is absolutely nothing wrong with these approaches. However, I am starting with a little bit of theory to point out the fact that the work of personal transformation has the potential be deep and profound. And, in this case, it can be extremely helpful to have a teacher or guide. Not everyone wants to go there, and that’s perfectly fine.

Why Having a Teacher At All Matters

The description that follows is what’s possible from the practice of yoga, as described by Patanjali in The Yoga Sutras, a text dated sometime between the 2d centuries B.C. and A.D. and considered by many to be the authoritative source text that describes the path of yoga. Historically the role of the teacher was to help the disciple to distinguish (viveka) temporal from eternal, relative from absolute, truth from fiction, and light from dark.

The tricky part of this work is that asmita, the ego—the overidentifiaction with I, me and mine—often wants to assert itself. And the truth of the matter is that the ego is not particularly adept at distinguishing truth, eternality, or the absolute. It is constantly grasping to what gives pleasure and trying to avoid that which is uncomfortable. This hell realm is known in yoga and Buddhism as avidya, which can be translated as ignorance or misunderstanding. A lot of the work of spiritual practice is a slow, gentle a dismantling of this misunderstanding associated with this excessive 'I-clinging.'

One might argue that the role of the guru was to make sure that this 'I-clinging' didn’t get in the way of the process of realization. That’s why most traditional schools of yoga or Buddhism emphasized the teacher-student relationship and not the practice of postures or meditation, alone. Without a teacher the aspirant risked misleading him or herself. He or she risked being led around by a craving for pleasure (raga) and a repulsion of discomfort (dvesa).

For Patanjali, yoga wasn't about feeling good, nor was it about feeling bad, either. It was a game of noticing that which was beyond pleasure and pain, clinging and aversion. It was a game of noticing essence, truth, and the absolute through a long, steady process of discernment. According to Patanjali, this process takes continuous practice (abhyasa) and the skill of non-clinging to pleasure or aversion to discomfort (vairagya) to be able to see clearly (1.12).

Very few of us naturally have this discipline. It's not easy to be with discomfort. Many of us can be with some discomfort. Few of us can be with it for extended periods of time. Nor are we apt to give up our 'I-clinging.' The process of letting go of what we cling to and being with what we’re averse to is counterintuitive. Additionally, the role of the guru presupposes that no matter how earnest we are, we can all get pretty slippery from time to time, and this can take us off of the path, even when we think we're on it. In other words, it can be pretty useful to have a relationship with someone who is committed to our growth and transformation, someone who can offer an honest reflection and guidance, too.

What Qualifies a Teacher?

And yet, we're living in a time when none of our teachers are fully illuminated. So what kind of criteria do we employ to choose someone to teach us? Do we choose a teacher because he or she has been on the path longer than we have? I don’t think that this is a valid reason to study with someone. Length of time does not qualify someone to be a teacher. So what standards shall we use to determine the qualification of a teacher?

▪ Years of practice?

▪ Years spent with the leader of the tradition?

▪ Displays of mastery?

▪ Teacher trainings?

What determines a qualified teacher? How the heck are we going to experience the full promise of yoga without someone who's qualified? And how are we to determine those qualifications?

Collaborative Relationship Designing

The problem is that it is impossible to be qualified to be a guru in this day and age. Gurus are 'fully-cooked,' so to speak. And most yoga and meditation teachers aren’t even close. We all have some clarity and a lot is still obscure. And while some of the prerequisites I list above can be helpful, I don’t think that any one of them can prepare a teacher to support a student on their path.

So I am starting with a basic premise: no one is perfectly qualified for the role of a teacher. Everyone in that role will be imperfect, flawed, and will make mistakes. It can be extremely helpful to start from the most basic recognition that our teachers will be and are human, people with good intentions who might fail us, nonetheless. Given that, how do we find ourselves in loving, trusting relationships with a teacher that can support us in our evolution along the path of yoga?

It starts with an agreement that I call relationship design. In relationship design, the context for a relationship is spelled out. In other words, it is a conscious contract that provides clear boundaries and a sense of direction for both teacher and student. When the agreement isn’t clear boundaries are crossed that can do damage.

I once had a really bad experience with a teacher in which I abdicated my own common sense in favor of my teacher’s common sense, thinking that her’s was ‘more enlightened’ than mine. By doing so, I made a decision that went totally against my own code of ethics. As a result, it kind of ruined me for a period and destroyed some significant relationships that meant a lot to me. Had we designed clearer boundaries along with the space where I could struggle with decisions myself, I might not have had to experience that suffering.

As a result of that experience, I am acutely aware that as a teacher, I cannot presuppose anything about my students wants or needs. In other words, I don’t know what’s best for my students. I am constantly asking my students to design with me what they need.

So when it comes to the relationship of teacher and student, it can help the process immensely for that relationship to be crystal clear. When it’s clear, both student and teacher can feel confident in their respective roles. The more committed student and teacher are to staying in communication, even and especially when the going gets rough, the more powerful that relationship can be. The more communication around the structure of that relationship, the safer it is for the student to delve inward and to know that he or she is supported. Additionally, it is critical that the relationship be continually tended to and be kept tidy. At the end of this piece, I give an example of how to start the conscious design of a student-teacher relationship. Have a look. Give it a try.

Humanity as the Doorway to a Sacred Friendship

Given the premise stated above, that no teacher is perfectly qualified to teach, it can be immensely helpful if both teacher and student start by recognizing the sanctity of the relationship. This relationship has the potential to be a form of yoga itself. It has the potential to be something quite unusual. It is one rooted in collaboration and based as much as possible in agreement, transparency, and intimacy. When both teacher and student fathom the honor of the relationship, both naturally hold one another to a particularly high standard.

In the few times that I taught classes for a friend in Tokyo, I have been struck by the way Japanese students regarded the sensei. As the teacher, I sensed the students’ reverence in a way that we in the West have difficulty comprehending. Given the level of surrender these students demonstrated, it would have been quite possible for me to take advantage of the situation, but I personally found it the case that I couldn’t help but step up in a way that I’d never stepped up as a teacher before. It was a great honor to be held as an authority, one that I couldn’t help but want to meet.

Likewise, I’ve experienced students walking into my classes with a sort of disregard for the role of the teacher. That’s perfectly fine. Not everyone would like a teacher, and many of us have experienced wounds at the hands of teachers. At the same time, without a regard for the sacredness of the roles, the teacher-student relationship takes on the quality of being a financial transaction, “payment for poses,” kind of a boring way of relating.

So honoring the sacredness is one part to this premise. Another part is that because the teacher is never perfectly qualified to teach, he or she can be regarded as human, warts and all. Some of us want our teachers to be extraordinary, but they're not. This is a real set up for failure, the teacher failing the student and visa versa. But when the student can recognize and interact with the teacher’s humanity, a true connection can start to be established, one that encourages a quality of human-centered friendship. It is rare to have a relationship where one’s humanity is honored. Very few of us experience relationships where we have permission to share all of ourselves and all parts are welcome.

Another boon associated with recognizing the teacher’s humanity is that it allows for both the teacher and the student to make mistakes. Relationships where mistakes are valued are dynamic and creative. Both people aren’t afraid to try things, to mess up, and to have breakthroughs. If the teacher has to play-it-safe for the sake of not upsetting the relationship, the relationship lacks a sort of dynamism that’s necessary to face the tough stuff that comes up on and off the mat.

The Shadow: Trust and Transparency

Both students and teachers have their limits of what they’re capable of working with in the shadow-work that shows up in the relationship. Playing with this edge can be very useful. For the teacher to take the student past the student’s edge, he or she must be confident in that territory him or herself. The teacher has no business shoving students into areas that are unfamiliar to the teacher. Below, I describe the prerequisites of teachers: self-study, peer feedback, and mentor feedback. All of these ensure that the teacher is doing the inner work necessary to support their students when they enter unfamiliar and uncomfortable territory.

Because the work of transformation confronts some of our most intimate spots, the student must be able to trust the teacher as much as possible. And so there has to be agreement between the teacher and student such that the student grants the teacher permission to head into a particular area, especially areas that feel vulnerable or scary. All it takes is a simple request, like “Is it okay if we go here?” Sometimes it can be helpful to create more dialogue before entering in.

In my first year as a yoga teacher, I ran into a situation that I am not proud of but feel that it’s pertinent to share. I had a student who was very, very proficient. I thought, “This guy is good. Let’s keep him going!” So I kept giving him pose after pose. Eventually he started to say stuff like, “I’m good. I don’t need any more, now.” But I kept adding poses on. At some point, he stopped coming to class, and I found out through the grapevine that he’d had a psychotic break that he considered a ‘kundalini rising.’ I was pushing, thinking that I knew best, when, in fact, he knew better. That experience taught me a lot about both trusting the wisdom of my students and keeping the conversation clear.

Throughout that work, it can be helpful to be transparent. Transparency isn’t just in the hands of the student. It can be extremely helpful and useful for the teacher to share when they’re confused, concerned or scared in relationship to what’s happening with a student. If the teacher has to pretend to be okay when he or she is not okay, it creates a low-level of distrust in the relationship. Transparency feels counterintuitive, but it’s honest. And being honest is an incredible gift that the teacher grants the relationship. It creates trust. When there is trust in the relationship, students and teachers enter into an intimate dialogue that is not misconstrued or taken advantage of by one or both parties. When there’s a lot of trust in a relationship, there is no telling what's possible for the student.

Selfless Service

The role of the teacher can be tricky. Occasionally students adore their teachers. Sometimes they loathe them. If the teacher is caught in the ‘popularity game,’ he or she will end up being manipulative. I've been caught in it, myself, from time-to-time. Occasionally, I will notice myself trying to use my charm to get students to like me. Once again, I am not proud of this, but it happens, and I don’t think I am the only teacher that’s fallen prey to wanting to be liked.

My proudest moments, though, have been when I've seen a student uncover something she or he'd been confused about or struggling with; when I've seen him or her diligently stick with something even when it was really uncomfortable; and in those moments when his or her wisdom, brilliance, and insight emerged with more clarity than that of a diamond.

In these moments my focus was not on me but on my students and their discovery process. That doesn't mean that I was perfectly objective, neutral, or impersonal. It just meant that my stance was first and foremost about my students, not about getting my personal wants and needs gratified. In short, the role of the teacher is one of self-less service for the sake of evoking the student’s evolution.

In Service to Evolution/ Granting the Respect of Autonomy

Part of the challenge this relationship faces is the fact that the student is paying the teacher to provide a service. In most service positions, the role of the server is to provide both care and comfort. While care and comfort may be useful qualities to cultivate in a teacher-student relationship, they cannot be the only qualities. If the student’s aspiration is transformational, then the relationship has to have room to be edgy and uncomfortable, as well. Without that, the relationship remains a ‘feel-good space,’ and this doesn’t really have anything to do with this path of distinguishing (vivieka) misunderstanding (avidya).

The teacher’s primary responsibility, then, is to the evolution of his or her students, not to the perpetuation avidya. This is where the role of the teacher can get tenuous. Manipulative teachers have been known to take advantage of this aspect to the role of the teacher. They’ve justified narcissistic behavior as something that’s “best for the student” when, in fact, it’s actually best for the teacher.

Being in service to the student’s evolution means that the teacher isn’t always in agreement with the student and is granted enough trust by the student to assert what needs to be asserted for the student’s growth. At the same time, the teacher grants the student the respect for their capacity to make decisions. Decisions of the student are of their own choosing and those decisions have to be respected.

Presupposing Our Students are Whole Rather Than Broken

Early in this discussion, I was speaking of the basic premise that no one is perfectly qualified for the role of a teacher. Similarly, it might also be useful to start from another premise, that students are whole and complete. They’re not broken. They don’t need to be fixed. In fact, the role of the teacher is to empower the student to trust him or herself, especially those parts that are innately wise, compassionate, and clear. This is a very unusual premise.

In most teacher-student relationships, the role of the teacher is to presuppose that the student has something wrong that needs to be altered, changed, or reworked. Rarely is this, in fact, the case. In the years that I have been teaching, I have rarely come across someone looking to be put back together again. When this is the case, psychiatry and psychotherapy can be extremely useful adjuncts to yoga therapy. But more often than not, students that have shown up to my classes are resourceful enough to make good decisions. Sometimes, it can be helpful for me to offer my expertise or to ask questions. Ultimately, I leave the decision in the hands of my students. If I regard my student either as broken, confused, or lost, it can be nearly impossible for him or her to access his or her own clarity. If the student cannot trust that something within is innately wise, then he or she will remain lost at sea.

I personally have had mentors and friends that have wanted to fix me at certain low-points in my life, people who had very good intentions, in fact. The problem with those relationships was that I would often abdicate my will to them, and while they may have steered me away from dangerous rapids, I never learned to either ride the rapids or to identify them in the distance.

When I can cultivate my students' confidence in their decision-making capacity, magic begins to happen for them. They begin to trust the wise parts of themselves to lead with clarity. So much of the baggage my students come in with is not from being egotistical. They don’t need to be knocked down and then eventually rebuilt. On the contrary, most of my students struggle with a degree of self-doubt, lacking the confidence that they know how to make good, sound decisions. When a teacher can cultivate a student’s innate strength, the process of clarifying (viveka) can take place.

Prerequisite: Svadhyaya: Continuously Growing and Evolving

If a teacher is not actually walking the path, he or she probably shouldn't be teaching it. Now, there's a lot of wiggle room in terms of what that means. If, for example, a teacher has a knee injury and doesn't practice various asanas, it doesn't mean that he or she is not qualified to teach. That's too literal a translation. The essence of what I am suggesting is that a teacher needs to be growing and evolving and in self-study (svadhyaya) in order to be able to help his or her students sort out their struggles. That really must be a prerequisite to teaching.

Prerequisite: Peer and Teacher/ Mentor Feedback

Another prerequisite must be that a teacher has a teacher or mentor of their own and a peer body to get honest feedback from. If the only people a teacher receives feedback from are his or her students, he or she risks becoming narcissistic or bipolar. Sometimes students love the teacher. Sometimes they don’t. And student feedback is biased, by nature. Peer and mentor feedback is not.

I've been very lucky in my years of teaching. I have had some smart teachers that I've partnered with who I've given permission to give it to me straight. It doesn't always feel so good to know when I am off base in a particular situation, either with a student or in the classroom, but with that feedback, I've learned a lot.

Having peers also gives one a sense of camaraderie, the sense that while the experiences of teaching are different, the essence of it is the same. I often find it comforting to have a space in my peer relationships where we can commiserate about the ups and downs of teaching. It normalizes experiences and situations where I do not feel confident.

Finally, having a teacher or mentor is critical for most teachers. It can be extremely useful to have someone to share confusions with, to seek clarification from, and to learn the art of deeper inquiry. Teachers need teachers and peers! These simple measures ward off the possibility of vainglory, a common pitfall associated with being in any role of authority.

A New Conversation

We’re living in different times, spiritually speaking, now that the age of the guru is over, but that does not mean we cannot experience the promise of yoga. It just means that we have to get a little creative. What I’ve presented above is very preliminary. I welcome all of your feedback. I have no intention of this being a ‘final statement,’ but, instead, something to evoke a conversation, something that we as a community have the courage to struggle with.

The Sangha May Be the Next Guru...

Before I end, I want to share a suggestion that Ken Wilbur posited, that the new guru is the sangha or community of like-minded individuals on the spiritual path together. I have actually had several experiences of living in and amongst communities. More often than not, there is no uniform agreement within it to use it as a tool for transformation. When there is, however, the experience can be absolutely brilliant and searing, at the same time.

I notice that we’re in a time when we long for community and yet we’re all frightened of it, of exposing ourselves and of being exposed. Likewise, many of our most painful moments have been in community, so we all have a lot of wounding around community, as well. But we’re also lonely, disconnected, and disjointed. And community can be a powerful place to reconnect, again. That’s why I think Wilbur might just be right. It might just be the perfect opportunity to wake us up to our true nature. Your thoughts?

Exercise: Designing a Relationship With Your Teacher

It may seem a bit artificial, at first, to have a ‘sit down’ with your teacher, especially if you have an ongoing relationship with him or her, however, the results can be very powerful and pivotal for you, him or her, and your practice. By the way, the design doesn’t end after the first conversation. It is constantly being re-negotiated. That way, the relationship remains both flexible and tidy. Below are just a few pondering questions that may give you a sense of what might be shared in such a conversation.

What exactly do you need and want from your teacher? From your practice? For yourself physically, emotionally, spiritually, etc.? If your relationship with him or her were to have a huge impact in your life what would it look like?

What’s your sense of what will really support your growth in the practice?

How do you want your teacher to handle you around risk taking? Does it help to push you, to be gentle with you, or to be somewhere in between?

When and how do you tend to get evasive? Do you stop coming to practice? Do you get angry? Do you shut down? How do you want your teacher to be with you when you do?

Where do you usually get stuck, either in your practice or in relationship? When you are stuck, what can he or she say that will bring you back to the present moment?

What does your teacher need from you in order to support your evolution?