When we lose a job, get a bad review, experience burn out, or our heart is broken, we often can’t help but experience a sense of groundlessness and paralysis. We struggle with meaning and end up feeling stuck. Who am I, now? How do I recover from the sense of frustration, overwhelm, or loss? In this post, I am going to suggest that what stops us is not the situations themselves. It’s never fun to lose a job or have our hearts broken, but there’s no inherent meaning in these losses. In other words, the circumstances of our lives don’t make us unhappy. Rather, our experience of them depends entirely on the meaning we bring to them. Some perspectives empower us when faced with even the most difficult of situations and some render us incapacitated. How we hold the circumstances of our lives can either grow us or take us down.

Part 1: Uncover your interpretations of the situations you find ourselves in.

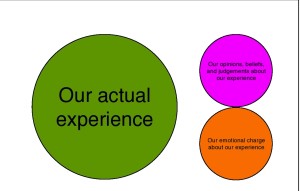

If we observe ourselves over a few days, we’ll notice an automatic, unconscious propensity to see that we’re always adding meaning to the experiences of our lives. We have the tendency to fit each experience that shows up into an ongoing story we have about our lives and who we are. In fact, rarely do we regard ourselves in relationship to the immediate circumstances we find ourselves in. Instead of relating directly to our experiences, we often just relate to our beliefs, opinions, and judgments about the experiences. And so when things fall apart, and we lose meaning in life, it can be incredibly helpful to reassess how we make meaning of our lives.

A 48-year old client, Mary, had been driven her whole life to make it big in the corporate world. A year ago she arrived at my office and declared: “I am totally burnt out and am just going through the motions of my life.” She didn’t sleep well; she’d gained ten pounds over the last few years; and her relationship with her girlfriend was suffering from her tendency to what she called “workaholic tendencies.” She’d been to a psychologist already, and while that work had clued her into why she felt stuck, it still didn’t propel the change she desperately needed.

When I asked Mary why she didn’t leave or alter her situation in her job, she responded that to do so felt like torture. Mary’s sense of purpose in life, up until that moment, revolved entirely around her work. Her sense of self and the qualities of her relationships went down when her work went down. Likewise, they went up when her work went well, not to mention the fact that she’d spent her whole life working her way to the top. Now that she’d finally made it to the “big time,” she couldn’t help but look around and scratch her head, asking, “Is this as good as it gets.” Her health and her personal relationships were suffering, and she found her colleagues, in fact, intolerable.

While Mary felt that to make a change would put her family in financial jeopardy, she knew, rationally speaking, that they’d do fine if she took a pay cut. She, like most of my clients use the “financial card,” as an excuse not to make a change. But when she looked closely, she was really afraid to upset her relationship with her girlfriend. As a child, her alcoholic mother had been inconsistent, sometimes present and sometimes altogether absent. When we looked at her “life’s story” it was obvious that she’d done everything in her power to give herself the security and safety that her mother constantly took away from her. She’d lived her life in service to accruing professional accolades so she wouldn’t feel the way she felt as a little girl, scared and destitute.

Part 2: Meet the feelings you’re avoiding.

To make profound, lasting change not only must we uncover the background stories that help us make meaning of our experiences, but we also must meet the nervous system’s response to the experiences. Embedded within each of our narratives is a statement like, “I never want to feel "x" again.” "X" might be loneliness, sadness, anger or fear. The narratives that live in the subtle background of our lives help us not only to succeed but also to avoid certain feelings. If we’re ever going to really transform, we have to be willing to meet the feelings we’ve spent a lifetime avoiding. In Mary’s case, her workaholism protected her from the fear of being destitute. As Mary examined her life’s narrative and discovered her propensity to be risk averse, she started to confront bodily feelings of terror: fluttering feelings in the chest, queasiness in the stomach, and a knot in the throat.

This part of the journey can be very uncomfortable and equally counterintuitive. Each of us spends a whole lifetime avoiding these feelings. Turning around and looking at them can be like turning around and facing the demon we swore off almost a lifetime ago. It takes incredible courage, even-mindedness, tenacity and compassion to ride the waves of emotional pain. And to do so can feel like this:

Heavy-heartedness… irritation in the chest… boredom… really heavy heartedness… tightness in the ribs…. burning rage…heat in the face…tight throat… boredom… fatigue… numbness… impatience and boredom…. nothing… nothing…nothing…hurt

Often times my clients will ask, “Why would I want to be with this shit?” Often my response is that to meet it is to transform it. To avoid it is to let it rule you.” If we don’t meet the body’s response, we miss a deep learning that our suffering has to show us. So as Mary met the fluttering, queasiness, and knots in one of our meetings, her “fear of change” lost its hold on her.

Part 3: Reinterpret the experience in such a way that it leaves you powerful.

At that point, she was no longer afraid to feel her terror. She could see that she didn’t need to be a workaholic her whole life in order to avoid “ending up broke, homeless, and alone.” Instead, she was at choice to create a new narrative, one that created possibility and that empowered her. When Mary tapped into the wiser and more intuitive parts of her being she could see that instead of her burn out being an obstacle, that it could be seen as an omen for change. “I could work less, maybe even go to yoga class, and have time to eat a meal with Donna [her girlfriend].” Instead of creating less safety, this crossroads might give her an opportunity to explore a new way of being in the world, one in which work wasn’t the only focus, but, instead, included family and intimacy.

Part 4: Make the insight real through action that leads to specific and measurable outcomes.

All it takes is a moment to see our situations in a light that renders us free, powerful, or expressed. But to make the changes necessary to fulfill this recognition a clear set of goals accompanied by practice. Once Mary committed to a change in her work, she started to look for new work opportunities, both within her corporation and outside. She made a point of meeting colleagues within her network. It took time and a lot of what I call “t.s.o.-ing”—trying shit out--to stumble upon an opportunity that excited her and gave her the flexibility she needed. She knew that she’d have to surrender some of the clout of her previous job, and so she also established some practices that made this transition easier on her nervous system.

Part 5: Practice mind-body techniques that support the nervous system and facilitate the change.

Mary and I co-created a morning ritual. Each morning she did some movement, whether it was yoga I taught her or taking a walk with her girlfriend. I also taught her a few simple meditations, which she could practice for 5-15 minutes. Finally she wrote in her journal on an inquiry I’d assign her each week. An inquiry is an open-ended question that can be answered from many different sides that gives new insights each way we look at it. One inquiry that uncovered a landmine of insight for her was, “What must I drop in order to gain something new?” This question helped her discover the confidence that she wasn’t just dropping off altogether but that her change would put her in touch with something new.

Slowly, over a six-month period, Mary discovered the right fit she’d been looking for in a new company. To an outsider, that move might have been seen as a demotion, but to her the move enhanced the quality of her life immensely. She worked less; had more time to explore new ways of relating and playing with her girlfriend; and found time for herself. Essentially, this move provided the breathing room Mary needed to replenish the well that had dried up inside of her.

Exercise

- Very briefly, write an account of your life and conclude with the situation you currently find yourself in. Keep the writing to a minimum of one page.

- Reread your brief account once.

- Notice how your life’s story influences the current circumstances you’re in. Does it empower or disempower your circumstances?

- Review your brief account, again, this time, reading your account out loud.

- Notice how it makes you feel in your head, throat, heart, belly, and genitals once you’ve completed the account. Do you notice any emotion, sensation, or charge in these areas of the body?

- If you notice that you do, read the account out loud, once again.

- Repeat steps 5 and 6 until any feeling of constraint has altogether gone away.

- Notice if there’s a new meaning you start to derive from the circumstances you find yourself in accompanied by new possibilities for yourself and your life.

- Write them down on a piece of paper.

- Hire a coach. A coach will hold you accountable to making the changes in life you sense you need to make. Don’t bother trying to do this part alone. Creating something new can be incredibly daunting. A good coach is really a skilled change agent. He or she will collaborate with you in designing practices that will make the process of change easier, fun, and intelligent, too.