The most challenging thing my clients face is how to deal with their emotions. Emotions can be such an inconvenience, especially the ones we're always trying to fix or overcome; the ones we beat ourselves up about; and those that we hide from others. These are what I consider the "shame-based emotions." We don't live in a world that has a great deal of intelligence around emotions. Some therapists encourage us to express them. As kids we're taught not to say anything, "if you don't have anything nice to say." When we see a friend or co-worker, and they ask, "How are you?" our reflexive responses tend to be, "Good. You?" When I was in my early-20's, I started to experiment with my responses to that question. Each time I gave a nuanced answer, like "I'm feeling blue today," the responses I'd get were often so weird and uncomfortable that I just stopped.

We all know that life isn't one smooth and happy ride, and yet we don't live in a culture or a time in history that acknowledges that fact. The very nature of emotion is that it isn't stable. The Greek god associated with our deeper emotions and dreams is Neptune. Neptune is also the god of water, oceans, and seas. The Greeks understood that our emotions were like the sea, untamable, unfathomable, and amorphous. We live in a culture and period that would like to and seeks to get a handle on everything around us. We might hang on to every word of a pundit that predicted the 2008 market crash. We might seek advice from self-help books and inspirational speakers. We even make big purchases, like homes and cars to feel secure. And we often won't rock the boat in challenging relationships and jobs, all so we won't feel certain emotions.

Why? We're downright afraid of our feelings, not all of them, but some, and especially the ones that we wouldn't describe when asked, "How are you doing today?" Part of the reason we're so averse to feeling shameful emotions is that we don't know how we'll handle them when they come up, or to put it another way, how they'll handle us. One of the emotions my client Tom avoids at all costs is sadness, and it's really getting to be a problem in his relationship with Jane, his wife. So when Jane inadvertently says something that hurts, he doesn't even notice that he's upset. From the outside, it's obvious. The expression on his face absolutely changes. And when she asks him what's upsetting him, he's quick to say, "Nothing. Nothing," and then adds, "Leave me alone!" At which point, he sulks for a few days until the mood passes. And when he finally emerges, he feels remorse and vows to never do it again, only to start that cycle over, again.

Tom isn't unusual. When we don't like a particular emotion, we do everything we can to avoid it, often to the point where we carry a great deal of shame around it. One client, Gina, feels so ashamed of the ways that she manipulates her boyfriend into "not leaving me." She can't help it, she claims, that she feels the urge to try to distract him from wanting to leave her. She says, "I just don't want to feel lonely." We're all afraid to feel certain emotions. That's the human experience. It's equally human that when we avoid our painful and shameful emotions, they tend to follow us like the plague. The Swiss psychiatrist, Carl Jung, famously said, "What you resist persists." Jung found that patients could not help but enlarge aspects of themselves that they wouldn't embrace. The more they hid, denied, or covered up that which they were ashamed of, the greater the problem became.

Throwing the Book at Ourselves

If we're ever going to change, if we're ever going to find a way of working with these painful emotions, we need to start by having a new relationship with them. We tend to regard emotions like anger, sadness, anxiety, jealousy, or loneliness as bad or wrong. Anything that's bad or wrong needs to be arrested or subdued. That's where shame enters. Shame is a form of self-loathing that we add to an already challenging situation. When we add shame to an emotion, it's a form of self-punishment. We penalize ourselves much like a judge or jury when we hold our emotions as either wrong or bad. And, in addition, we continue to paralyze ourselves, making it impossible to learn or evolve from the experiences we're in. In fact, when we throw the book at ourselves like this, we end up as Tom keeps ending up, repeating the same experience again and again.

Emotion is a reply or a response to a stimulus. That's really all it is. And when we try to overcome, deny, or attack ourselves for even having the emotion, we miss out on the deeper learning the emotion is trying to make known. To become adept at listening to our emotions is to gain access to our inner experience and to be led into an inner life. What's required of us is something absolutely counterintuitive. What's needed is that we develop the knack for staying aware of our emotions when they come up and restrain ourselves from judging them and reacting to them.

Refraining from Reaction

Contrary to popular belief, our emotions are not the thoughts we have about the way we feel. These thoughts are the stories we tell ourselves, which are made up of our opinions, judgements, and beliefs. The domain of emotion is totally different from the domain of thought. Emotions, in fact, are really quite a physical phenomena. We feel our emotions. We feel them in our bodies. As soon as we feel emotions, especially painful ones, we tend to react to them by forming stories about their source and almost simultaneously seek strategies to try to get away from them. This process of feeling--->identification---> reaction happens so quickly that unless we're really paying attention, we rarely notice it happening. Why? Because the brain does not distinguish emotional pain from physical pain. For the brain, they are one and the same. And so we reflexively try to get away from pain. The only problem is that emotions, even the painful ones, aren't eradicated through these knee-jerk reactions. In fact, they tend to create more problems.

Lisa, came to coaching because her husband is threatening to leave her; he claims that she's "not present in the relationship." Through a little inquiry, we quickly discovered that she's angry with him for not showing up as an equal partner. But she doesn't want to "rock the boat" because she fears her anger and the devastation it might cause. Her father was quite verbally abusive to her mother and sister, and she's afraid of the damage she'll cause. She's so habituated to avoiding her anger, that she's almost completely checked out of all her relationships, especially the one that means the most to her. In other words, as soon as she feels anger, she identifies it as wrong or bad, and all at once becomes absent. And she's so habituated to this reaction that she doesn't even notice it happening. It's gotten to the point, now, where she can barely be in the same room as her husband.

Realizing We're Triggered

Before Lisa was ever going to be able to work with her feelings of anger, she was going to have to learn to slow down enough to notice the emotions or feelings she was reacting to. The only way she would be able to do that was to let the domain of thoughts go and enter into the domain of feelings, bodily feelings. It took some coaxing, but as she got habituated to meeting the emotions in her body, she stopped reacting to them in the same way. Anyone can easily develop the ability to observe painful emotions that come up when we're triggered. Being triggered literally evokes a biochemical experience, a cascade of feelings, usually uncomfortable, accompanied by shallow and rapid breathing. If we develop the knack for staying attuned to the body and/or breath, we can short-circuit a lot of the drama of our lives, especially the fabrications we make up that result from our knee-jerk reactions. Our body and breath give us warning signals to alert us to a painful emotion long before we've reacted to it, and it's gotten out of control.

Body-Scan

One of the easiest ways to discover our emotions in the body is to locate them with a body-scan. When we scan the body, we do a quick scan for gross, uncomfortable sensations from head to toe. We scan the surface and interior of of the body from top to bottom and back to front; so, a body scan might look like this:

Head, face, neck, throat, shoulders, arms, hands, chest, upper back, belly, mid and lower back, pelvis, genitals, legs, and feet.

My client, Jenny, tends to feel her anger in the hollow in the back of her knees. Others feel it in the chest as a tightness or a heaviness. Some feel it like a stuck feeling in their bellies that keeps moving around or like a piece of steak caught in the throat. Given the fact that our bodies are the ground for this internal feedback, it's critical that we develop a relationship with them, to develop a daily habit of attuning ourselves to the inner framework of our bodies, to actually wanting to know what's happening inside of us, even when we experience an unpleasant feeling. We have to alter the language, "What's wrong, here?" to, "What's here, now?"...Pause...Feel...and then, "What's here, now." ...Pause...Feel...and then, "What's here, now."

Short Exercise

Briefly scan your body from head to toe and notice if any feelings or sensations stand out. Allow yourself to stay with a sensation for a minute or two with a quality of curiosity. "What's here?" Just locate whatever emotions or sensations are in your body, and stay with one or two of the sensations for a sustained period of time.

Laser-Focused Attention and Soft-Global Attention

My 20's were tumultuous years. I spent a good deal of those years feeling lonely and lost, emotions which exacerbated an already sensitive gut. The only thing that would quell the discomfort sometimes was lying prone on the floor or in bed, closing my eyes and just feeling my way through the he knots in my belly. That's what they felt like on first glance. Then the initial tightness around the gut would give way to subtler sensation in the belly, almost the feeling of scurrying mice, until, at some point, I could pinpoint a locus, a central point from which all the sensations were emanating from. It was as if all of the tightness in and around the belly was a sort of bracing or guarding to protect this central, vulnerable point. When we learn to meet our emotions in the physical form of our bodies, it initially feels gross. If we're patient, the guarding or protection fades, and the sensations require subtler and subtler awareness. If we keep our awareness connected to the domain of the body, we will begin to notice a variety of sensation with accompanying emotions.

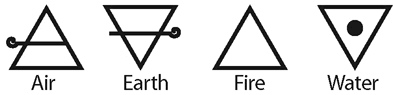

The sensations tend to require a laser-like focus. All the attention is pointed toward one single spot. Occasionally, however, it can be useful to alternate between a concentrated, focused attention and a softer, full-bodied awareness. This second type of awareness allows us to be conscious of the underlying mood or tone and gives us a sense of what's changing overall.The laser focused awareness gives us an almost microscopic view of subtle body sensations. It can sometimes be useful to label the sensations associated with laser-focused awareness and the emotions associated with soft-global awareness as a way to stay present and to stay out of the storyline in our heads. Here is a very simple labeling classification that comes from the five elements:

- Air:

- laser-focused awareness sensations: floaty, light, and moving

- soft-global awareness emotion: afraid, anxious, apprehensive, fearful, frightened, hesitant, jittery, nervous, overwhelmed, panicky, and shaky

- Earth:

- laser-focused awareness sensations: heavy, fixed, grounded, stuck

- soft-global awareness emotion: apathetic, blah, dull, fatigued, lethargic, listless, numb, stuck

- Fire:

- laser-focused awareness sensations: cold, cool, hot, and warm

- soft-global awareness emotion: agitated, angry, annoyed, bitter, cold, disgusted, disheartened, dismayed, edgy, exasperated, harried, irate, irked, irritated, and mad

- Water:

- laser-focused awareness sensations: deep, moist, sticky

- soft-global awareness emotion: anguished, blue, brokenhearted, dejected, despair, disappointed, downhearted, gloomy, jealous, morose, mournful, and sad

Staying with Curiosity and Noticing Change

The wisdom and insight that we discover from paying attention in this way requires a sustained form of looking along with a quality of curiosity. In other words, if we just notice how we feel and draw quick conclusions as to why we feel what we do, we don't actually get the learning our difficult emotions have the potential to reveal to us. And because they're uncomfortable and our brain seeks quick resolutions to their occurrence, there's a propensity for all of us to try to figure them out quickly, so we don't have to feel them. When we bring our attention to the body sensations and immediately try to understand, make sense of, or grasp why we're feeling the way we feel, we short-circuit the deeper learning our emotions offer us. If we're trying to meet our discomfort with the aim of getting rid of or fixing the feelings with answers and justification, we enact a subtle form of rejecting our feelings.

Instead, what I want to posit about painful emotions is that it can be immensely helpful to incorporate patience, curiosity, and a quality of welcoming into the inquiry. Curiosity tends to lower the risk associated with meeting our edge. It also opens us up to being surprised to find unexpected truths. Finally, it's child-like and exciting. When we are welcoming of painful emotions, we soften into and invite them in, rather than tightening and resisting them. Welcoming of painful emotions can be immensely challenging, especially if we are prone to avoiding them. It can sometimes be helpful to have an outside support who can help us feel safe enough to welcome. If an outsider isn't present, we can also occasionally bring a gentle and caring hand to the area of the body where we feel our emotional pain, caressing the area in a nurturing way. I sometimes even have clients hold a pillow or teddy bear to feel connected to a child-like welcoming.

When I first tried to teach my client, Kevin, how to pay attention to his body's experience of anxiety rather than trying to understand it, he closed his eyes, felt inward and reported a tightness in his chest. He then opened his eyes and said, "Oh I am nervous. It's probably because I have a lot on my mind today." And while this is an absolutely valid interpretation of his experience, it's still a speculation on the cause of his anxiety. So I asked Kevin to welcome the tightness in his chest and to start to get curious not about "why" he was feeling this way but just to be curious about the sensations. He closed his eyes again, and I asked him, "What are you noticing, now?" "Well, the tightness is gone. I don't feel anything in my chest." And so he opened his eyes, again. So I said, "Great, no more tightness in your chest. What's there, now?" Reluctantly, he closed his eyes, again, and after a long pause, he settled inside and said, "I didn't realize this before, but I guess I feel sadness." "Where do you feel sadness?" I asked. He pointed to his upper belly." "Great," I said. "Not great that you feel sad. Great that you're noticing that. Stay with it and see where it takes you." So we sat quietly for a minute or two while he stayed with his inner feelings and sensations. At some point I noticed tears dropping down his cheeks. "What's happening?" I asked. "I just really miss Jenny," his ex-girlfriend.

Kevin's story is very revealing about the journey into our emotions. We tend to just scrape the surface of them when we try to understand them before we've given ourselves time to feel them. When we bring both an inquisitiveness and a welcoming to the feeling experience within our bodies for a sustained period of time, even when the feelings are uncomfortable and, at times, unbearable, we start to notice that they change, thus, giving us access to richer emotions that reveal a greater depth to our inner experience. And if we stay with the feeling experience, rather than avoid it or fix it, the first thing we'll notice is that it changes.

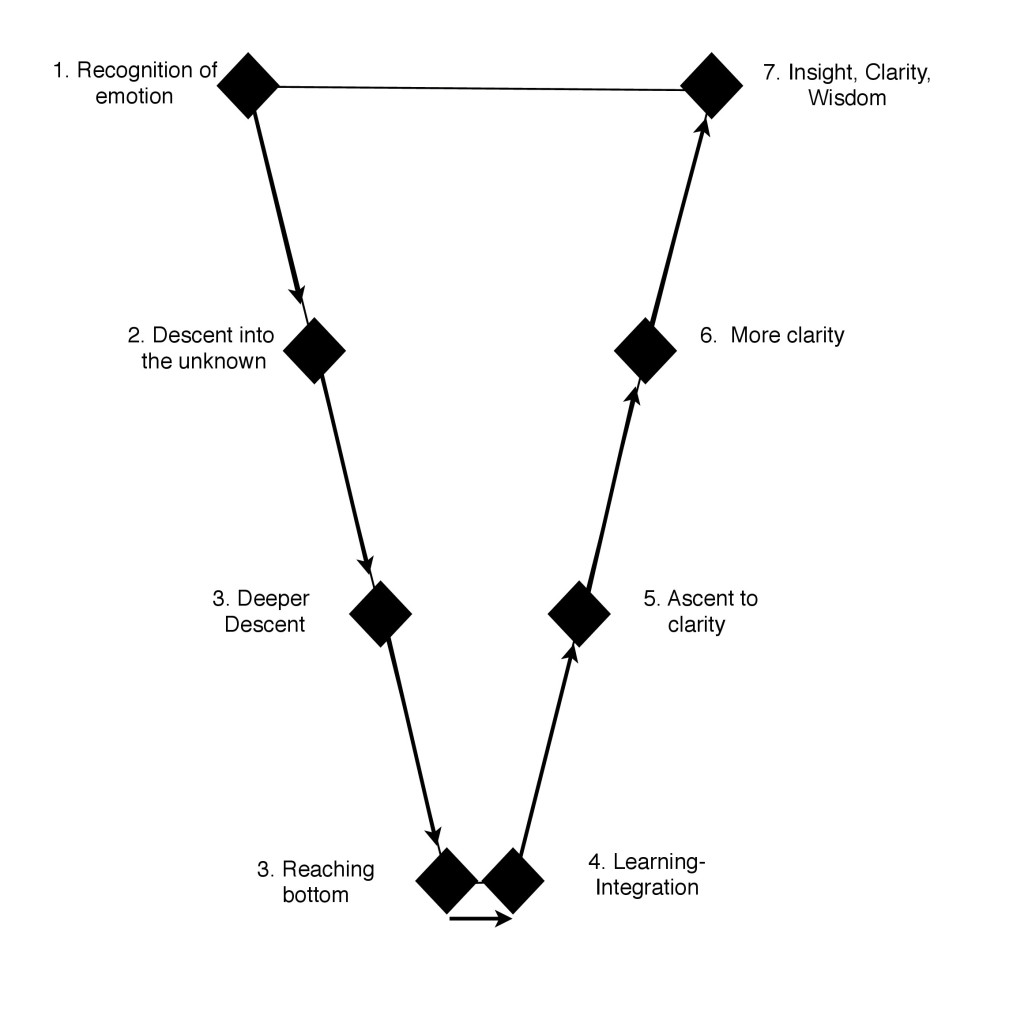

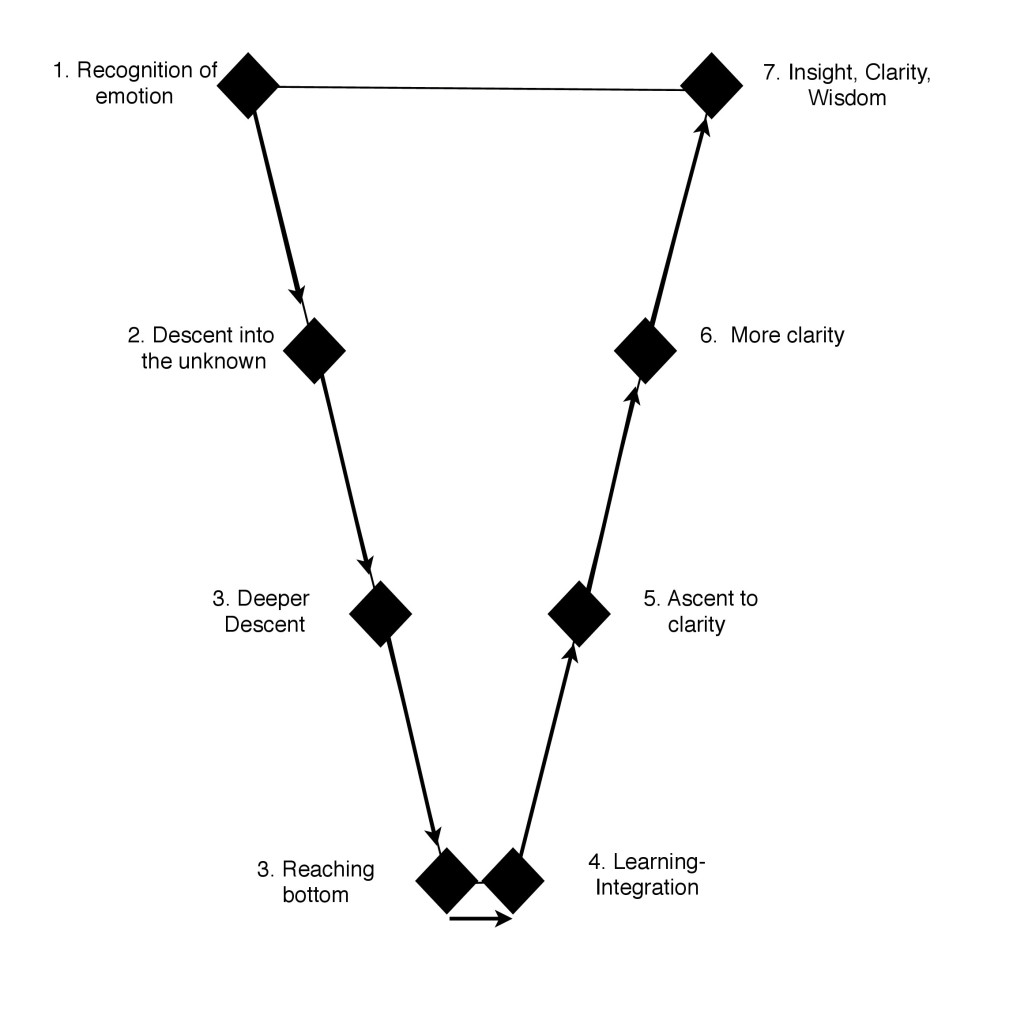

Surrendering to the Descent

That's the nature of all emotions and sensations; they're constantly changing. What the next sensation will be can't be predicted. Nevertheless, I tend to see a pattern in my clients when they develop the skill set of looking. There's a kind of descent that initially takes place, and for some of my novice clients, that descent can be a bit unnerving. As we go down, in, and through to the heart of the emotions and sensations that we've spent years and sometimes even a lifetime trying to get rid of, fix, overcome, or hide from, it can be a little scary. Even worse, it can feel like the descent is never ending. Below is a visual representation of this experience.

The essence of the model above is that before we're ever going to develop wisdom, clarity, and insight, we have to be willing to surrender to the feeling experience, tracking it as it changes from stuck and tight fear, to hot and burning anger, back to fear, and then all the way to sticky and heavy gloominess. While it sometimes doesn't feel like it will ever come, we do, in fact, always reach a bottom, sometimes in minutes, sometimes in hours, and other times in days. At some point we get there, and once there, it can feel chaotic or as if something inside is breaking apart. And for some of us, it can feel like labor. Nevertheless, when we reach the bottom, we experience a sort of disintegration and reintegration. While the experience is a whole lot less pleasurable than sex, reaching bottom is almost the same as reaching orgasm. We can no longer hold the energy or intensity, and, thus, experience a sort of spilling over into a new perspective and sometimes even a new life. This moment is really the moment of transformation we all seek. It's the moment some people wait a lifetime for. In many ways our painful emotions are invitations to this new awareness.

This breakthrough is described quite well by the Tao Te Ching, "When I let go of what I am, I become what I might be." Letting go, in this sense, is really letting ourselves go into the feeling experience of the painful or difficult emotions so that we can incorporate and include what we have previously prevented, resisted, or tried to overcome. Once we've reached the bottom of the ride down, we start to develop the capacity to be comfortable with the emotion. It no longer runs us. We stop feeling the need to react to it. More significantly, as we integrate, rather than reject, we experience more wholeness, more clarity, and a vastly different outlook on life. If we allow them, our emotions can be powerful enough to completely alter the way we experience the world.

Don't Do It Alone

Because this descent can be unnerving, it can be immensely helpful to have a guide along the way, especially someone who isn't particularly biased, like a family member or a friend. A well-reputed mind-body coach, somatic therapist, or teacher who has years of experience with clients can ease this process for us. Other places where we might develop the knack for dropping into the domain of the body are mindful dance classes, yoga classes, and meditation classes and retreats. It's important that the classes be less oriented around performance or competition, but, instead, the focus is each individual's one's own internal and personal experience.

Brief Summary

- Noticing uncomfortable feelings accompanied by shallow and rapid breathing when we're triggered.

- Scan the body from head to toe looking for gross and uncomfortable sensations.

- Alternating laser focused attention and soft, global attention.

- Identifying the elemental quality of the sensations: air, earth, fire, and water.

- Staying with curiosity and openness and noticing change.

- Surrendering to the descent until we've reached the bottom.

- Integration, insight, and clarity,

If you'd like to learn more skillful means of working with shameful emotions, please contact me for a complimentary assessment:

[jbutton color="orange" size="large" link="/free-consult"]Get a Complimentary Assessment[/jbutton]