A group of friends and I have started to gather at my house monthly to take a deeper dive into Yoga than the kind we get when we go to the yoga studio or even when we do a teacher training. The problem with teacher trainings is that there's so much to cover in terms of content, that we don't have a lot of time to linger on some of the deeper questions, like what on earth is yoga about? Or what's yoga to me? Or how did the ancients view yoga and spirituality? And how does it pertain to my life? It is my sense that we all have to ask these questions, to not just accept techniques like asanas (yoga postures) or meditation without an analytical consideration.

A group of friends and I have started to gather at my house monthly to take a deeper dive into Yoga than the kind we get when we go to the yoga studio or even when we do a teacher training. The problem with teacher trainings is that there's so much to cover in terms of content, that we don't have a lot of time to linger on some of the deeper questions, like what on earth is yoga about? Or what's yoga to me? Or how did the ancients view yoga and spirituality? And how does it pertain to my life? It is my sense that we all have to ask these questions, to not just accept techniques like asanas (yoga postures) or meditation without an analytical consideration.

And because Yoga has the propensity to be embodied and non-analytical, we're not encouraged to go here a lot. My teacher, Pattabhi Jois,is often quoted as saying, "Yoga is 99% practice, 1% theory." How often do we hear the instruction, "Drop the the thought and return to the body," or "Your thoughts are like passing clouds. Notice the thought, and come back to the breath." This is really the heart of spiritual practice, just noticing. And most practice, if it's effective, takes us out of our thinking, comparing, and analytical mind and into a more intuitive, sensing, feeling, and non-thinking place.

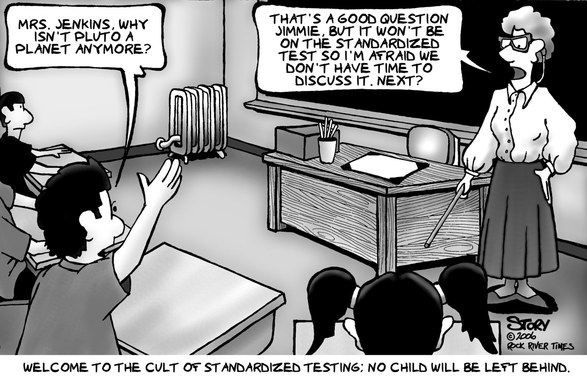

But that's not to say that the spiritual experience is, strictly speaking, a non-thinking experience. Actually, there's a lot of thought, in fact, thousands of years of thought, about the spiritual life and the spiritual experience that we can draw from. There are a ton of maps written by those who have walked the path before us that we can use to understand and make sense of our own journey. It is not only important but should be mandatory for all of us who are deeply seeking to understand the traditions we come from. That way we can start to contextualize them and make sense of them. More importantly, I think it's imperative that we develop a critical eye for our spiritual practice and the teaching associated with it, so we can choose a path that takes us to where we need to go rather than where we're told we should go by a teacher, a teaching, or a community.

The Sutras Through a Critical Eye

As I was preparing for our last gathering, I came across an interesting podcast by Matthew Remski that really had me questioning how much authority I wanted to place in The Yoga Sutras as a map for my spiritual practice. Remski points out some of Patanjali's weird views. Examples include:

- The idea that Yoga is about such a complete separation of awareness (purusa) and nature (prakriti), that it veers in the direction of disembodied, spiritual bypass. In other words, the cessation of the fluctuations of consciousness (1:2) lead to a recognition that one's true identity is not this body; this entity I call me; or these relationships I surround myself with. These are all fluctuations within awareness. Through a gradual process of detachment, we see that these things are ephemeral, and thus, not eternal. The awareness (purusa) that notices these things that arise, stay for awhile, and pass away is eternal, and, thus, our true identity. Extreme form of non-attachment, like the one espoused in The Yoga Sutras, has the potential to validate the avoidance of practical challenges or difficult or painful feelings or memories. This stark dualism, separating awareness and all the things within it tends to unground people and unseat them from their innate wisdom.

- The fourth chapter, Kaivalya Pada, commonly translated as chapter on liberation is a mistranslation. Pada means subject. Kaivalya actually means perfect isolation; thus, one of the end goals of a good yoga practitioner, according to Patanjali, is to detach so much from nature (prakriti) so as to separate from society, as a whole. Yoga was heavily influenced by the monasticism of Buddhism and Jainism. In fact, the ethical precepts, the yamas and the niyamas, come from the Jains who believed that separation was a necessary ideal to experience complete liberation, that to be in contact with others leaves the yogi vulnerable to the negative karma of another. In our everyday language, this is another way of saying that liberation requires that we stay away from others so as not to pick up on their bad vibe.

- The book is chalk-full of magical thinking. For example, intense forms of absorption lead to one's capacity to fly or inhabit the body of another and make that body move.

Remski's analysis--which is brilliant by the way--forces us to look twice at this text that we yogis tend to hold with reverence. Without a doubt, much of the instruction in The Sutras is erudite and brilliant. Developing a capacity to practice anything with non-attachment (vairagya) (1.15) is a simple and brilliant instruction on how to learn anything. The tools that the Sutras offer us on how to witness and what to witness are fabulous instruction for each of us who would like to develop greater capacity for objectivity.

But how far do we intend to take this process? In its most extreme form, it could lead us away from our relationships, away from community, and either into monastic life or a cave in the Himlayas. Or maybe what we're looking for is just an hour in the day "where you don’t know what was in the newspapers that morning, you don’t know who your friends are, you don’t know what you owe anybody, you don’t know what anybody owes to you. This is a place where you can simply experience and bring forth what you are and what you might be. (Campbell, Joseph; Bill Moyers (2011-05-18). The Power of Myth (p. 115). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.)

Bringing Old Texts to Life

As I said before, I'm not suggesting that we ignore the classic texts. They're giving us hints that can help us immensely on the journey. But if we are on the path, we have to take responsibility for our journey. Doing so requires that we look with a critical eye. When we accept these maps on faith we sometimes end up in places we never intended to be. A lot of the orthodox approaches within the Buddhist and Yogic tradition posits the notion that because we're too rife with avidya (misunderstanding, misapprehension, or spiritual ignorance), we cannot possibly see what will help or hinder us on the journey. That's why we need not question the authority of the teacher, the teaching, or the community but, instead to have faith in their innate validity.

There's a third approach to working with the teachings of a tradition. We don't take them at face value, and we don't ignore them. Instead, we struggle with them. We see them as texts written by human beings, like you and me, and who were writing for a particular audience living in a particular moment in history with a unique set of struggles. And then we work with the text to separate that which is essential truth for us from that which is particular to the times and perspective of the writer. And then we try to make sense of it for the current situation we find ourselves in. This how a tradition becomes a living, breathing, and evolving thing. And if you consider it, we are the critical link to the evolution of the tradition. How each of us interprets and makes sense of any tradition determines how it will be carried forth from one generation to the next. In short, to go through this process is to take responsibility not only for our spiritual path, but to create new maps, maps that one day will influence seekers, like us.