In the last two blogs I've written, I have been discussing Sat-Chit-Ananda, an ancient yogic compound that describes the experience of yoga. Each of the three Sanskrit words, sat, chit, and ananda, all speak of different aspects of the one, unitive experience called yoga. It's almost like a description of the Holy Trinity, which connotes the three various qualities and aspects of the one God. The same is true of Sat-Chit-Ananda. While each word is a world unto itself, the experience of yoga occurs when all three of these worlds take form at the very same moment.

Non-Doing

In this blog, I intend to write about the Sanskrit root, sat. Sat is really the part of the compound of Sat-Chit-Ananda that has less doing or action than chit. Chit is the active part that we play with our minds. It's how we direct it. And, specifically, we direct the mind on 'what is,' as opposed to the way we think it is; the way it might be; or the way think it ought to be. Chit is a direct form of seeing without interpretation. Sat, on the other hand is not active. It's just who we are, essentially, when we’re not trying.

It is an interesting word because it can mean two different things when we translate it from Sanskrit to English. On one end of the spectrum, it can be used to describe something that is either true, right, and/or good. On the other end of the spectrum, it can mean being, existing, or abiding in. So we have these two very different usages of the word, and yet when we join both together, we have something along the lines of "true being" or "abiding in the truth." So the term, sat, is pointing to a sort of presence or quality of being that is right good, and true.

Authentic Self

So when we put it together sat is really who we are at the very core of ourselves, namely the authentic self. Given the intensity of change and the fast-paced times we're in, it isn't always easy to connect to or even know who we truly are. We're so hyper-stimulated that to look for and discover what this is seems only for the elite, for those few monks and yogis who live in monasteries and caves somewhere in the Himalayas. The problem is that if we don’t start to look to see who we authentically are, we run the risk of flitting about life, never feeling truly anchored to a sense of the sacredness of who we truly are.

Initiation

So where do we start? How do we uncover our authentic selves? In yoga we start from where we are. It doesn’t matter whether we’re coming from a bright place or a dark one. I personally started practicing Ashtanga from a place of tragedy. My journey began more than 20 years ago when my brother committed suicide. Why is suffering such a powerful initiator? Because the experience of suffering wakes us up to our vulnerability. It’s often from this place that we go looking for answers. Some of us, like my wife, was initiated into her journey into Ashtanga Yoga in order to “ get a six-pack abs.” It doesn’t matter where we start. The journey toward the heart of who we are on the level of being, our authentic self, starts where we start.

Asmita

We all start the journey with an identity that you and I call, “me.” Patanjali’s Sutras call an excessive sense of me, asmita. Asmita is often translated as “ego” but is, in fact, more like that part of us that overly identifies with our opinions, our beliefs, our moods, and, in general, the way we think things are. When we’re locked in our fixed ideas, we may feel superficially safe, but if given even half-a-scare, a loss, or physical pain, we immediately come face-to-face with our fragility, our aloneness in the world, and sometimes, even, the meaninglessness of life. And it’s worse when what we thought we knew or understood is, all of a sudden, pulled away from us.

When I lost my brother, everything I thought I knew about life, got mangled. In one moment, nothing made sense anymore. I’m not just speaking about the horrible grief of losing a brother, which is heartbreaking in and of itself. I’m also noting the sense of having the rug pulled out from the identity of who I thought I was. My asmita wasn’t able to cope with the stark reality that my brother could end his life so tragically.

When the asmita is particularly strong in us, we feel a sense of separateness from our world. We feel a sort of disconnect. That can show up as malaise, frustration, low-grade anxiety, bouts of rage, and the sense that something just doesn’t feel right. We often regard these feelings, as “bad news,” but, in yoga, we regard them as, in fact, “good news.” The reason why is that if we apply consciousness or chit to them for any sustained amount of time, we begin to develop deeper insight into who we are.

If we do not face what’s right in front of us, these feelings can give us the sense that the world has no luster. This is what in Hindu philosophy is called maya, the illusion of our separateness. But illusion and insight are two sides of the same coin. Through the application of chit, the veil of illusion opens up to a sense of greater unity or harmony with the world we live in and the relationships we have, both to ourselves and others.

A coaching client has been struggling with low-grade anxiety for the last three days. His wife and he are in a disagreement. His employee just can’t seem to get things done the way he’s requested. His boss is acting like a ‘bull in a china shop.’ He’s been trying to get a product ready for market by traveling back and forth from San Francisco to Southern California every week for the last six months. He feels anchorless and reports feeling like “a ship out to sea.” As we sat in conversation, I asked him, “What are you feeling?”

“Anxiety.”

“Where?”

“In my chest and belly.”

“What does it feel like in there?”

“It feels hollow in my belly, and at the base is this heavy stone.”

“How heavy?”

“Like one big brick.”

“Great. Just notice that.”

After a few minutes… “What are you noticing, now?”

“The heaviness is gone.”

“What’s here, now?”

“Sadness and fear.”

“What does that feel like in the body?”

And so the conversation went on like this for about 20 minutes. We just kept applying chit to the body, checking in every once in awhile to report on what he was experiencing. After a period of time, the intensity of feeling shifted from anxiety, fear, and sadness to clarity, insight, and wisdom. At that point, he realized that he needed to reestablish trust with the people around him, that he’d been so unmoored by trying to get the product to market, that he hadn’t really given his relationships the time and energy they deserved. “I’ve always prided myself as a ‘relationship guy,’ and I’ve been stuck on just getting it done. Boy have I been missing the boat.”

In the case of my client, anxiety, which is normally regarded as something that needs to be overcome, was, in fact, a great teacher. Because he had the courage to apply chit to the discomfort in his body, he was able to wake up to see how his overemphasis on accomplishment rather than relationship was affecting not just others but mainly himself because he wasn’t being congruent with his essential self. That’s sat. It’s often through pain and discomfort that we wake up or our reminded of who we fundamentally are and what’s truly important to us.

Gratitude, Chutzpah and The Long Slog

But it’s not just suffering that puts us in touch with sat. It also shows up when we’re connected to the practice of gratitude. I feel a deep sense of gratitude that I have the space and time to write about topics that mean a lot to me. Writing is my gratitude practice. I feel more truly who I am when I can slow down enough to distill my thoughts and feelings into something that can be read by others.

For many of us, passion is a doorway into Sat. It takes incredible passion to be willing to face ourselves on the mat the way we do. Even though Guruji used to say that Ashtanga is universal, that it’s for everyone, I’ve always been clear that it isn’t for the faint of heart. You need the fire of passion burning in you to face the things we face on the mat. Sometimes we show up and feel a llittle broken, sometimes we face limitlessness, but we’re always face-to-face with ourselves. The practice becomes the mirror expression of how we are each day. And it takes incredible chutzpah to look each day. It’s this passion for practice that uncovers an aspect of our sat.

One of our relatively new yoga students is in the stage of her practice that I call “The Long Slog.” It’s the point where she’s experienced the initial thrill of learning a portion of the primary series, but now she needs to practice what she’s learned in a continuous manner to both develop some mastery and, more importantly, to really extract the deeper learning that the sequence has to offer her. This is the point in the practice where we unpeel the layers of holding, old injury, childhood wounding, and boredom, lots of boredom. During “The Long Slog” many new students give up because they see the work that’s in front of them, and it appears daunting. Others recognize it and see the value.

During ‘The Long Slog” we’re doing the same thing over and over and over again, but each day it’s different than yesterday’s practice, last weeks practice, or the practice we had a year ago. We start to see what it is that is constantly changing. Behind all the change, we cannot help but notice a part of ourselves that always remains the same. That’s sat, the one self, the eternal part of us, the one that never changes.

Sat and Chit, Being and Doing

Recently, I’ve been watching old Ashtanga video footage on Youtube. One of the videos that I recently became reacquainted with and that has always particularly moved me is the 1993 Yoga Works footage of Guruji leading a class with Tim Miller, Chuck Miller, Maty Ezraty, Richard Freeman, Eddie Stern, and Karen Haberman. I saw this video a few years after I started practicing Ashtanga. This was a time when all-things-Ashtanga absolutely thrilled me, and I remember being totally enthralled by those ‘masters’ on the screen. It must’ve been a bit like what it was to see the Beatles on Ed Sullivan or Led Zeppelin at the Greek Theater. What I most loved--and still love--about that video was that even though they were practicing the same sequence, each was approaching the practice from a very different place. To me, Tim was all heart. Chuck was depth. Eddie was laser intensity. Richard was pure grace. Maty was fiery passion. Karen was herculean strength. I could not help but see a portion of their authentic selves shine through in the footage. What I saw and still see in those yogis and yoginis was the merging of doing and being. This is the same thing as sat and chit being one.

It isn’t yoga to me when I see yogis practicing the way pianists practice scales, without connection to their essence. It’s a lot like those people who go to the gym, turn the Stair Master on high, and look up at the Today’s Show to see what Ann Curry is wearing today. It’s vapid. It’s like saying, “I have a body somewhere below me that needs to be exercise, but I am somewhere else. And, hey, at least it’s yoga.” When I see this 1993 footage, I am reminded that when sat and chit are one, something beautiful and graceful emerges that is both pleasing to the eye and puts us in touch with our sense of aliveness, ananda, and our essence, sat.

When the Walls Come Tumblin’ Down

Ashtanga is physically very hard. There’s a ton to do and remember. From the moment we arrive on the mat until the moment we leave, we are in an incredibly detailed choreographed set of movements, breath cycles, internal contractions, and endorphins, lots of endorphins. By the time we complete the practice, a defensive part of the psyche is sometimes so pooped out that our authentic selves just magically appear. In other words, the practice exhausts us in such a way that a lot of walls we put up that keep us away from ourselves and the world around us fall down. Many of us experience this in savasana. Sometimes we experience it for 30 minutes after practice. Sometimes it lasts for a whole day.

One of our new students clearly had it for seconds last Monday. As I was leaving the studio, I noticed him looking at the sky in a meditative way for about 5 seconds. Most of us just glance up to notice whether it’s sunny, cloudy, or rainy. We don’t often really look. Something about this students practice allowed a part of his automatic responses to not take root in that moment. It was actually breathtaking for me to watch him appreciate the simple beauty of the blue sky.

Remember...Forget...Remember...Forget...Remember...Forget

In those rare moments when sat, chit, and ananda appear simultaneously together, the moment is sublime. Once we’ve experienced this union, we can’t help but keep looking for it. Why? Because it feels both expanded and natural, transcendental and normal, and deeply and profoundly true, good, and right. We often label ourselves by what we do, and we describe ourselves by the lives we’ve previously lived. When sat coexists with chit and ananda, we know who we truly are.

And the game of sat is really a game of remembering and forgetting. Remembering who we essentially are and forgetting who we are, remembering and forgetting. Once we think we’ve understood it, we haven’t. In order to continue to remember, it can help a lot to make choices from this place, to follow the thread of resonance that sat presents. When we do, we cannot help but create lives for ourselves that are true, good, and authentic. In the next blog, I will speak more about how to choose sat as a way to remember more than we forget.

Sat-Chit-Ananda Series

This is the third part of a four-part series that explores the experience of yoga. Be sure to check out the other posts

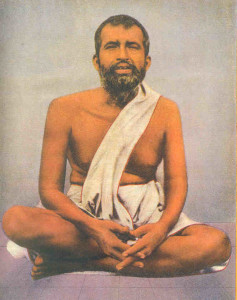

At some point, all of us face the need to evolve. It's almost an imperative in spiritual practice that if we are to experience the aliveness of life, we must keep growing. And sometimes that means letting go of what no longer serves us or that we serve whole heartedly. If we don't let go, we suffer. And yet doing so can be grueling. I wanted to share a teaching from 'The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna' about knowing when to let go. Ramakrishna was a 19th century, Indian mystic.

At some point, all of us face the need to evolve. It's almost an imperative in spiritual practice that if we are to experience the aliveness of life, we must keep growing. And sometimes that means letting go of what no longer serves us or that we serve whole heartedly. If we don't let go, we suffer. And yet doing so can be grueling. I wanted to share a teaching from 'The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna' about knowing when to let go. Ramakrishna was a 19th century, Indian mystic.