Below, is an email exchange I had with a friend in the Ashtanga community, someone who is struggling to find a way into her practice such that it supports her fatigue and depression. I share it because I have the sense that many practitioners silently struggle with these very issues, and I do not believe that the teaching community adequately speaks into these issues. Often the instruction students receive is, “Keep practicing. It will change.” And so many fatigued and frustrated Ashtangis, just keep doing the same practice over and over hoping for a different outcome. Many, however, quit. Ashtanga is a powerful practice, but there can be an ethos within the community that is unforgiving. There isn’t a lot of space for those who need to deviate from the standard practice. It is not uncommon for students to essentially get the message: “You either do it the way it’s taught in Mysore, or you’re not welcome in this room.”

I share this dialogue for those people who have not been able to find the space within the world of Ashtanga to know that an Ashtanga practice does not have to look just one way and that there is a way for the practice to support you, no matter where you are in your life.

Dear Chad,

I have had chronic fatigue for many years, and used to find my Ashtanga practice helpful with my energy levels, but lately, I’ve been struggling with the intensity of the practice and have been asking myself, “What the heck am I actually doing?” I do think the Primary Series is very detoxifying, but it wasn't until I went back on antidepressants that I had any kind of ability to maintain my practice. I have been off of them again for 1 year and want to keep it that way.

However my fatigue returns when I try to expand my practice, and my self-practice at home is never very energized. I feel I need the energy of others in order to really push through my energy issues. And now that I’m in my mid-40’s, I’ve been asking myself, “How am I going to maintain this practice?” Lately, I am always on that line of questioning because it seems that without the pills I cannot maintain my energy, and I am committed to keeping myself off medications.

At this time the support of a community and teacher would be so helpful, but I cannot seem to find it; in fact, I have been greatly disappointed by folks within the tradition who I admire, people I thought would understand and point me in a particular direction. They’ve neither been kind nor helpful. If you could offer me some advice on how to proceed I would be very grateful.

Thanks,

T

Dear T.

Many within the tradition we come from, unfortunately, promote the notion that we should be able to maintain a vigorous practice no matter what stage of development we're in, no matter how healthy or unhealthy we are. And that's just not a viable, life-long approach to practice. The practice that suited me in my early 20’s, for example, no longer fits for me in my 40s. A mature perspective on practice recognizes that yoga should support our health and well-being no matter where we are in life.

When I first started learning the practice, I was 19 years old, so it helped me immensely to have a place to direct all of my energies, both positive and not so positive. Without it those anxious times might have been met with a lot more self-destructive patterns, like drinking, drugs, and self-loathing. Having the structure to get up early each morning, to show up on that mat and practice strongly each day was the perfect solution for all that anxiety, self-doubt, and agitation that seemed to be central to my 20s and early 30’s. But as I’ve gotten older, practicing like that zaps me.

I’ve recently stopped practicing Advanced A. I find that it stresses me out physically and emotionally. As I transition into my early 40’s, I notice that all of the arm balances make my neck, shoulders, and upper-back ache and tax my energy. I am at the stage of life where I want to have enough energy to give to my wife, our family, my clients, and my community, and it is a lot to manage. At some point in the last few years I woke up to the fact that I did not want to keep giving all my energy to my practice. I wanted my practice to be able to support me, to support my life, to support my pursuits.

And these days, I’m just starting to be okay with the fact that my practice might look different each day. I tend to stay on the six day per week schedule, but I no longer beat myself up if I don’t get to it that often. If I, at the very least, get on my mat four days a week, I feel like I’m on track. After all, I’m not trying to “kill it.” I’m not pushing into the next pose or the next series. I’m maintaining my health, vitality, and clarity to face my life. While I practice primary and intermediate series most of those days, I may or may not complete the whole series of postures. I usually jump back between sides, but when I don’t have the energy, I don’t push it.

I especially don’t push it when I have an injury, am sick, or don’t get enough sleep. Melissa, my wife was up all night with the flu last week, which meant that I was up, too. When I got on my mat the next morning, my head was spinning. I wasn't sure if I was coming down with the flu, myself. So after the Ashtanga Invocation, instead of starting Suryanamaskar A, all I had the energy to do was to take padmasana; do ujjayi pranayama for about 30 minutes; and then take a 45-minute savasana. Yep, that was my practice. And, yes, I still consider that Ashtanga Yoga. I did not, in fact, get sick. I had eight clients that day, and had I not taken care of myself, I would have been a mess.

It is my sense that the practice continues to evolve as we get older. When I was in Mysore in 2005, I was told that someone I was practicing with in the shala in his mid-50’s was taking anti-inflammatory drugs in order to continue practicing Advanced A and B. His practice looked quite acrobatic for someone his age, but was that practice supporting him or was he supporting it? What’s clear to me is that as the body evolves, so should we.

Krishnamacharya, Pattabhi Jois’ teacher, divided yoga practice into various categories, called krama, which means a step used to achieve a particular goal. As we get older, our orientation moves from athletic perfection (siksasana krama) to maintaining our health and preserving our youth (raksasana krama). Eventually, our orientation moves to adhyamatya krama, or spiritual matters. (1) We tend to move our practice in this direction in the time of life we in the West tend of think of as retirement. It occurs in our culture when we are in our 60’s or 70’s. Our focus turns toward questions about the meaning of life. And so the orientation is less in the way of getting and staying strong and flexible in the body. I am not suggesting that it is unimportant to maintain health and vitality as we age, but that the 60’s onward are about developing wisdom, and that comes about primarily through stillness practices, like meditation. (2)

I cannot personally speak about this stage of development because I am not there. I do know several Ashtanga practitioners in their late-50’s and 60’s who do not keep the same practice they kept when they were in their 20s, 30s, and 40s, but they’re not very public about how their practices have changed; in fact, about a year ago, I asked an old friend who has been practicing since the 70s if he would be willing to be interviewed for this very question, but he declined. He did not want to expose himself to criticism. I completely understand his perspective. When someone speaks about altering the practice to even the slightest degree, some people who have elected themselves to be the “yoga police” within the community launch in with vitriolic abuse. Nevertheless, I do sense that it would be very healing for all of us to learn how our teachers and mentors evolved their practices to account for the physical, emotional, and spiritual changes that occur with aging.

As far as I can see, T, you can take the practice we're taught and break it into component parts that support you energetically and spiritually. Maybe one day you skip all jump-backs and jump-throughs to prevent fatigue from setting in. Maybe on another, you practice only a few postures paying particular attention to your breath and bandhas and only go as far as you can keep your attention. When you notice it flagging, you stop. Maybe on another day, you wake up feeling ungrounded, so you just do the standing sequence, holding each posture for 10-20 breaths. Or maybe the mood needs lifting, so you focus on back bending, chest openers, and emphasize inhales and inhale retentions. The variations are endless. What’s required is the willingness to take the dive, to experiment.

Yes, it can be helpful to have a teacher who has already walked down this path, someone who can show you the way, and it can also be extremely helpful to have a place with group support where your experimentation is welcome, but there are not many Mysore rooms or teachers that are ready for a student like you, not yet, at least. So you have to be willing to develop a home practice and then also be equally willing to take risks, read, and just keep showing up on your mat with curiosity.

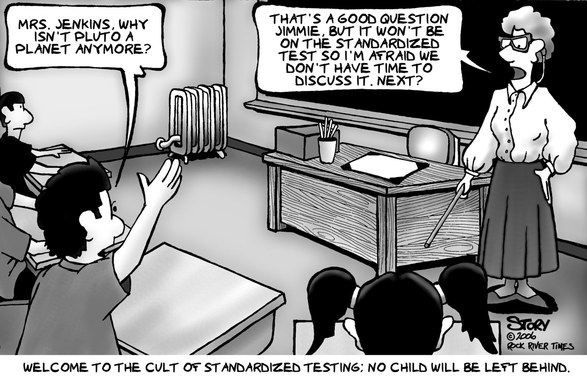

In closing, I recently heard about this experiment called the Asch Paradigm where they put 10 people in a room. 9 of the people were shills. 1 was not. They showed all 10 cards with lines of different lengths. Two of the lines were clearly of equal length (Exhibit 1 and B) while the other two (A and C) were not.

The researchers asked the nine shills to claim that two badly mismatched lines (B and C) were actually the same, and that the actual twins (Exhibit 1 and A) were total misfits. The one person who was not a shill almost always went along with the other 9 members. Why? When they quizzed the victims of peer pressure, it turned out that many had done far more than simply go along to get along. They had actually shaped their perceptions, not with the reality in front of them, but with the consensus of the multitude. (3)

In short, what I'm suggesting is that you're not weird or unusual in your experience of the practice. That you're fatigued from it is pretty common. My question to you is whether you have the guts to trust your own intuitive sense that something is off and find an approach that supports your well-being and that supports your mood. That can be a huge challenge, especially if you're used to the support of the Mysore room to carry your practice as well as the support of a teacher and friends who share a mutual love for the system. It's hard not only to stand on your own, but to trust your innate knowing when everyone around you is telling you that you’re crazy when, in fact, you’re not.

I hope this helps.

Chad

Footnotes:

(1) So for example, B.K.S. Iyengar reported that “In 1978, after my 60th birthday celebration, my guru (Sri T. Krishnamacharya) advised me to devote time to meditation and to reduce my physical strain.” (Iyengar, B.K.S., Astadala Yogamala. New Delhi: Allied Publishers Limited. 2001)

(2) I’m not suggestion just because one has reached a certain age, they should stop doing the Ashtanga series. If someone has the inclination, time, and energy to devote to progressing through the series and they’re no longer young, by all means, I think it is important to follow that urge. It can be incredibly life affirming to practice advanced postures and to push the limits on what’s possible in this human form.