Earlier this week, I noticed that a bunch of my yoga friends on Facebook were commenting on some notes from a conference led by Sharath Jois. Sharath was giving a talk partly on sirsana (headstand). According to the notes that were so generously shared with all of us by Megan Riley, sirsana not only benefits circulation, but it "help[s] to draw our Amrita Bindu, these golden drops of nectar that, over time, fall down into our digestive fire, back to the head. [Amrita Bindu] drops as we age, and keeping it from burning away will keep us looking youthful and bright."

When I read this, my first reaction was, "Come on? A golden nectar that keeps us looking youthful and bright? What's this? Sounds superstitious to me." I could understand how a headstand could alter circulation, facilitating the return of pooled blood into the heart, but no science books that I'd come across had located or described golden drops of nectar within the head that when preserved through inversions keep us young, if not immortal, and radiant.

And yet, over the years of being a student of this tradition, I've come to realize that it might not be useful to just blatantly disregard the teaching just because it doesn't fit within my immediate understanding of reality. I've grown so much over the years as a human being and yoga student by grappling with concepts within the tradition that initially seemed foreign, otherworldly, and, at times, magical. When I've applied a practice of openness, curiosity, and experimentation to the teachings, I've tended to learn more and, at the same time, grow more. This isn't always easy for me to do. In fact, this notion of Amrita Bindu is part and parcel of various aspects within the tradition that, even to this day, still trip me up. Examples include:

- Ashtanga comes from an ancient text, The Yoga Korunta, written by Vamana Rishi, and is 5000 years old.

- It is 'incorrect method' to alter sequencing, modify the poses, or include props into The Practice other than adjustments.

- Do not practice on moon days because injuries on these days take twice as long to heal.

- When taking padmasana (lotus posture), the left leg should always be on top of the right. This clears the liver and spleen, straightens the spinal column, and helps the aspirant to maintain strength.

- Yoga students should eat primarily milk, ghee, and chapatis in order to develop strength because they promote a sattvic (clear) mind and strong body. Avoid eating many vegetables. Do not eat garlic, onions, tomatoes, or any meat.

- Drink coffee before practicing yoga because coffee is prana (life force).

- Don’t wash or wipe your sweat off but massage it into the body after practice in order to make the body strong and light.

- Men and women should only have sex:1) at night 2) when the man's left nostril is open 3) when the woman is between the fourth and sixteenth days of her menstrual cycle 4) only for the sake of having children 5) only when lawfully wedded.

- Never breathe through the mouth because it creates heart troubles.

- When you make the Darth Vader sound associated with Ashtanga breathing--also known as ujayi pranayama, but technically within the Ashtanga tradition, the term ujayi is restricted to a form of pranayama practiced separately from asana practice-- you increase internal heat, which thins the blood and purifies it.

- Mula bandha should not be restricted to asana (posture) practice alone but should be practiced while walking, talking, sleeping, and eating in order to maintain mind control.

Not Saying, "Yes" But Not Saying, "No," Either

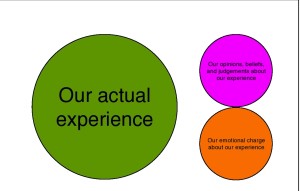

On first blush, a lot of the rules mentioned above seem a little dogmatic; at times, occult; and, in almost all cases, exotic. I want to suggest that as Western educated yogis that we both refrain from blatantly disregarding them, and at the same time, not thoughtlessly absorbing them. Instead, I think it's important that we learn to develop the practice of applying critical thinking.

While there's no doubt that The Practice is powerfully life-changing, it does not mean that as practitioners of this method that we completely surrender our capacity to discriminate. It's important to be able to question what we're told. As far as I am concerned, I think it's a sign of a mature practitioner that uses her hesitancy as a tool to learn. Without it, we run the risk of being pollyanna-ish about everything that's presented to us. If we don't simultaneously apply the qualities of openness and curiosity, however, we run the risk of never growing out of our small bubble, of being arrogant, and of being lazy. Being stuck on being right and knowing it all is a form of laziness. The student never has to discover her misconceptions, nor does she have to struggle to learn.

And learning is rarely a passive phenomena. From where I stand, I can see that it would take me several lifetimes to learn all that this practice has to impart. Guruji's knowledge was vast and his teachings, which, on the surface, sometimes seem simple, are, in fact, quite deep. I have no doubt that to grasp the depth of the wisdom he imparted would take me many lifetimes. And because I don't come from his or Sharath's culture, I have to struggle to put their words and experience into my life and into terms that make sense for me. I can't just take them at face value. I have to try to make sense of them on my terms.

I think that that's part of what makes this practice so challenging for us Westerners. Terms, concepts, and world views are, at times, diametrically different in India than they are in the West. There's no doubt that we're all after the same things: peace, wisdom, compassion, and happiness, but how we express the path can be quite different. What's required as Western students of this tradition is the work of bridging the cultural divide by translating The Practice into terms that are both culturally and individually relevant so that they simultaneously breathe new life into our practices and perspectives on life.

Santa Claus Isn't Coming Down the Chimney Anymore

I sometimes wish that I could just have faith in someone else's words and let that be enough. I don't think I am alone in my longing. Having faith doesn't necessarily come easy to a lot of us in the West. For a lot of us, faith is like still believing in Santa Claus. At some point we all discover that he doesn't necessarily come down the chimney, that that's just something someone told us. And when we're old enough to discover this, it can be heartbreaking, but that experience awakens us to something else, the capacity to question what we're told. And this questioning can be very useful in the times we're living in, especially when our advertisers or our politicians are trying to get us to buy or vote for things that don't serve us.

But at the same time, in spite of our capacity to apply critical thinking, we in the West aren't, on the whole, necessarily a happy culture. We may be rational, but we're missing a sense of meaning, a sense of order to life. A lot of what we face in the West is a sort of spiritual wasteland. So when we look to lineage-based traditions from another culture, like Ashtanga, that are rooted in the wisdom of antiquity, we can't help but want to find the magic, again.

I remember when I used to think that if I did my asana practice six days a week for the rest of my life, "All was coming." At some point along the way, though, I discovered that Santa wasn't coming down the chimney of my practice, either. There is no doubt that the practice is an immensely helpful force in my life and has been over the last twenty years, but it's not perfect. It has helped me overcome the trauma of my brother's suicide; it introduced me to an international family of like-minded people; and it has created a lot of meaning and order to my life. But it doesn't and can't solve all the woes that ail me.

I completely understand the urge to want to buy the system and everything about it as perfect. It's so tempting to do. And over the years, I've seen lots of my yoga friends initially do this but eventually, something snaps. I can't tell you how many former vegetarians I've known in The Practice, or people who were incessantly talking about postures and what pose they were on in Mysore, and then, at some point, drop the thing altogether.

One friend of mine had spent a few years living and studying in Mysore. Like me and like so many others I know, he came to Ashtanga, initially, to heal old wounds. Early on in his studies, he spoke about, practiced, and taught Ashtanga Yoga with the fervor of a "true believer." Every other sentence out of his mouth would be a quote from Guruji: "Slowly, slowy, you take." "In-correct!!!" "Yes, yes, you come!" Eventually, this parroting became a little creepy to me, and I kind of wanted to tell him to cut the crap, but eventually, he got injured. And while he struggled to continue to practice and teach, at some point the message and the method stopped making sense to him. His conscience would no longer allow him to teach or practice what he eventually saw as "a bunch of bullshit." This is just one story of many more stories I could recount of friends who started gung-ho, but eventually recognizing that something was askew.

Having Faith in Skepticism

From my perspective, what was askew was not necessarily the teaching, but that my friend didn't maintain his healthy skepticism. When we surrender our capacity to discriminate, we actually end up suppressing a significant part of our identities, something that we need in order to both get through life, but also to maintain our sanity within the confines of groupthink. In short, it's really a significantly important part of The Practice to question and struggle with the discrepancies between what's taught and what we, in fact, experience. One of my favorite quotes on this matter comes from one of the most renowned Indian yoga gurus in history, Siddhattha Gotama Buddha. He said,

"Do not believe in anything simply because you have heard it. Do not believe in anything simply because it is spoken and rumored by many. Do not believe in anything simply because it is found written in your religious books. Do not believe in anything merely on the authority of your teachers and elders. Do not believe in traditions because they have been handed down for many generations."

To me, the Buddha is saying that part of our job as yogis on the path is to use the practice as the vehicle to work with the teachings. We don't just buy whatever we're told. We use our practice as the testing grounds to experiment with the hypotheses presented to us.

Making Sense of Apparent Nonsense

If we're truly on the path, not only do we not have the luxury of taking things at face value, but we also don't get to blatantly put everything that doesn't fit into our worldview into the categories, "false," "wrong," or "superstitious." A former student of ours used to come to samasthiti (even standing posture) each morning to chant the opening prayer, but he refused to join in with the other voices. When I asked him why he didn't, he said indignantly, "I am not a Hindu. I don't want to say something that I don't believe in." So I decided to share an English translation of the prayer with him.

When I asked him what he thought of the opening prayer after reading the translation, he said, "Yeah, like I said, I don't want to chant a Hindu prayer." So instead of leaving it there, I suggested that we go over the translation of the prayer together. Instead of leaving the prayer in the category of "someone else's sentiments," I wanted him to see where, in fact, the words might actually mean something to him.

So we spoke about the first verse of the invocation, which is about having gratitude for the teacher that helps us overcome samsara. Samsara is often translated as conditioned existence. It's this idea that we keep being reborn from one lifetime to the next until we've conquered our misapprehension. Once we've done so, we've attained suahavabodhe (happiness in the purity of mind). He liked the idea of overcoming delusion and uncovering happiness, but he couldn't get his head around reincarnation.

So, I suggested that he not get stuck on lifetimes, either before or after his current life, but that he see that within this very lifetime he was in, he'd already experienced numerous iterations of himself. While something of him had always remained the same, he'd also been a child, a teenager, and a young adult. As a result of these changes, he'd experienced several lifetimes within this very lifetime, and he was bound to experience more. He liked that notion that within the various stages of life he had left, that he could intend to overcome the delusions of samsara.

He had a hard time with the notion of bowing down to a guru, though. "I don't want to give anyone else that much power." So I suggested a few other ways of holding this notion of the guru, either the guru could be an inner part of his psyche that was innately wise, resourceful, and powerful. I also suggested that the practice, itself could be seen as the guru, that through the practice, itself, confusions, doubts, and suffering could be overcome. "Yes, he said, that's true. I feel so much calmer on the days I practice. It's on these days that I make better decisions. Yeah, the practice is my guru!"

That was the first verse.

When we took on the second verse, he had a lot more difficulty. The second verse of the Ashtanga invocation is about prostrating to the author of the Yoga Sutras, Patanjali, and visualizing him as a serpent with a thousand heads with arms holding a conch, a wheel, and a sword. On first blush, he said, "This reminds me of pictures of Hindu gods and goddesses with multiple arms. I am spiritual, but I am not religious, and I don't want to pray to a god, certainly not someone else's."

I explained that the verse is an homage to the author of The Yoga Sutras, Patanjali, and is suggesting that the philosophical backdrop of The Practice rests in The Sutras. Patanjali is mythologically considered to be a serpent that serves as the asana (seat or yoga posture) of Vishnu, the god of infinity. As the serpent, he's holding a conch, a wheel, and a weapon or sword. The conch is symbolic of the music of the cosmos that calls yogis to live noble lives; the wheel represents the wheel of dharma, or the order of life (as opposed to the randomness); the weapon or sword represents the power of discriminating good from bad, right from wrong, and truth from fiction.

I suggested that he hold the image of the serpent with multiple arms as representative of various values. First, that our practice is rooted in a system of thought that is deep, profound, and life enhancing, that it's not just another form of calisthenics or aerobics. Second, the symbol of Patanjali as a serpent that acts as the seat of Vishnu might mean that by sitting or abiding in the wisdom of this philosophy, that we have access to our infinite nature. The symbols that the serpent holds call us forth to make life enhancing choices, ones that are noble, moral, and truthful.

My student liked my translation, but to him the Hindu iconography was just "too Indian." And, he didn't, in fact, know anything about Patanjali. He'd heard of The Yoga Sutras, but hadn't read them or studied them, so he couldn't see the significance of venerating someone or the words of someone that didn't mean anything to him. So, he agreed to chant the first verse of the invocation and refrain from speaking the second verse. As far as I was concerned, I could completely appreciate his decision. I also asked him if he'd be up to studying the Yoga Sutras, which he said he'd consider. I appreciated that he'd walked through this process with me. He didn't just throw the whole thing out as, "Hindu mumbo-jumbo." He actually did the work. And in doing so, he could start to chant the first verse of the invocation without feeling like a fake.

For many of us, we need to do this. It's important to parse out what is, in fact, meant by the teachings. We need them translated in terms that make sense to our lives. It isn't in anyway shameful to not understand the teachings. It's only shameful to simply pass them off as nonsense without making any effort, without seeking to meet the essence of the teachings and to allow them to grow us.

I realize that the list that I made at the beginning of this blog is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of what we as Western Ashtanga yogis must struggle with if we are to continue to use our discriminative minds within The Practice. It takes a sort of courage to give up the magical notion that Ashtanga is some divine sequence of movements and postures passed down to us from time immemorial by a saintly being who lived in a time and a place when everything and everyone was perfect and wise. That'd be nice if that were the case, but it's unlikely that that's true. But that doesn't mean that The Practice is all hooey, either. It just means that we get to and, in fact, have to do our work, including practice and study, to find a way in that makes sense and, at the same time makes our lives and the lives of those around us better.